By Alenka Mrakovčić We probably agree that language use is among the most taken-for-granted aspects of our daily lives. But what if within the language you use, you cannot find language uses that would represent you and your experience? How, then, does this impact the way you exist in the world? This was one of my main questions when I started working on my master thesis about trans experiences of language use.

Let us think about language use regarding gender. The act of assigning the sex to infants – “It’s a girl” or “It’s a boy” (or, in case of intersex infants with “ambiguously” shaped genitals: “We’ll have to do some more tests to assign this baby one of the binary sex categories”) – is the beginning of establishing the binary-coded language use that we then most probably have to conform to throughout our early years and beyond. This becomes problematic, however, when our experience of gender doesn’t quite fit in these categories of cis-heteronormativity.

In order to explore the experiences of oppressive gendered language use, I talked to 10 trans and gender non-conforming Slovenian and Spanish speakers. I would like to present here a glimpse of how they make their wor(l)ds more bearable, comfortable and inclusive.

Slovenian has grammatical gender, and so these issues become particularly visible. A very wide range of words is gendered and offers little room for gender-neutral or gender-inclusive uses in standard language use. So what happens when only feminine/masculine forms in language do not feel right to you? “The whole world is one big reminder that you don’t fit in. And you have to somehow shape it, so that it is still bearable and comfortable for you,” Maj told me. Others explain there is a “missing space” to express freely and to feel understood. Azul: “I feel like I don’t have any space, I don’t have a place where to be, where to express myself, where I’ll be understood, where, above all, I’ll be respected.” Although these themes sound similar, they are a bit different. I put them side by side to highlight how people who have a common experience, live, feel and describe it in different ways.

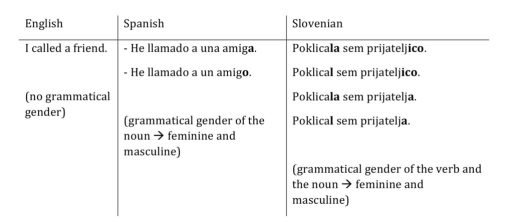

For those not acquainted with grammatical gender, here is a brief example of how a particular gender comes about in grammar. In Slovenian, to refer to yourself or any other (human) person, which requires use of verbs and adjectives etc., there are only two binary gendered forms you can use: feminine and masculine. In Spanish, there are no gendered forms for verbs. Here is an example, compared with English.

The meaning of grammatical gender and gender that people usually assume is informed by the rigid gender binary. Especially in the case of languages where it is hard to overcome grammatical gender, it will still be used by people who do not identify with either of the binary genders. But the way they use language may also resist the binary forms and their binary meanings, or encompass the development of new forms of language use to make space for their expressions. Individuals or communities explore, reclaim and almost invent different language uses. Ironically, these forms of resistance to the binary-normative language use are often disputed and ridiculed by the very same gatekeepers that preach about language being “alive” and ever-changing.

In Spanish, there is, grammatically, a relatively simple solution: the binary morphemes “a” (feminine) and “o” (masculine), can be replaced by “e”, which can sound both inclusive of all genders when used to refer to groups of people, and as gender-neutral grammatical gender, when used by or for specific person (“He llamado a une amigue.”, where une amigue refers to a person of any gender or a non-binary person).

In Slovenian, where the gendered endings and declensions offer less simple changes, a solution in spoken language still presents a challenge. But in writing, the two endings can be connected by underscores (“Poklical_a sem prijatelja_ico.”), and this has become common among trans and other activist communities. In spoken language, the two forms can be said one after another in the same sentence, or by exchanging feminine and masculine forms throughout the text. Two Slovenian speakers, whom I talked to, tried the latter but over time people gradually stopped using both forms and again referred to them with one grammatical gender, that which “matches” their sex assigned at birth. This felt invalidating and uncomfortable.

Other participants also spoke of invalidation. It seems that once a person finds language uses that fit their experience, they also have to fight for it in order to be deemed valid and respected by cis and often also trans people. One of the Spanish speakers had had many experiences when they were told by trans people who identify as binary, that their gender-neutral language use is wrong. “They feel this as a threat, I guess,” said Rio. “That my existence can invalidate their existence […] and I understand it, but the truth is that I’ve lived a lot of transphobia exactly because of that, curiously.”

Not only finding, but also claiming and using alternative language uses can often feel lonely. Yet at the same time this way of self-validating our own language use seems like a powerful way to achieve long-term change. It is only by respecting, acknowledging and adopting these strategies more widely, the people who resist the arbitrary binary and cis-normative frames can become visible and respected. After all, we are in charge of and responsible for our language use. Language doesn’t dictate us – however much we’d like to resort to its seemingly rigid structures.

Alenka Mrakovčić is a recent graduate of Erasmus Mundus Women’s and Gender studies (GEMMA) Master’s degree from Central European University and University of Oviedo. In this blog post they share a few insights from her Master’s thesis research “Speaking out of the cistem. Non-cisgender people’s language use in Slovenian and Spanish”(2018).